There is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic has sent shock waves across the globe unprecedented in recent history. Few countries were prepared to deal with the chain reactions that led to loss of life, serious disruptions in economic activities, and loss of livelihoods for millions. As countries struggle to recover from these shocks, it would be important to reflect on some of the lessons that could be learned and identify areas of priorities to address the challenges.

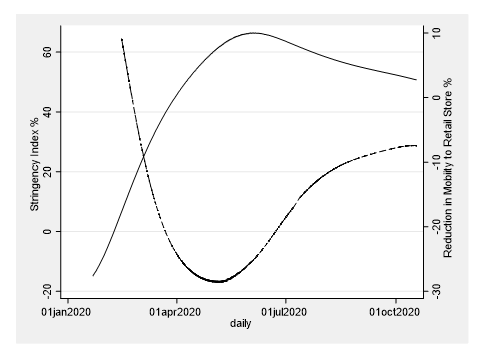

Once WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, many African countries heeded the guidelines provided by WHO in tackling the spread of the SARS-2 virus. The major guidelines included a) restrictions of mobility of people, within and between countries; b) restrictions of large gatherings, including weddings, funerals, rallies, sport games, church services, etc., to enforce social distancing; c) closure of offices, schools, businesses to avoid flareups, d) increase testing and tracing; e) handwashing and wearing of masks, etc. Some institutions, such as the Oxford University developed the Stringency Index to capture how countries have been coping with the COVID-19 pandemic since it all begun in around February 2020[1]. As can be seen in Figure 1, Stringency Index for Africa started climbing very sharply around February 2020, reached its peak sometime in 1st of July 2020 and started declining slowly until October 2020. Most countries started relaxing movements after November but reintroduced stringency measures in the wake of new wave of COVID-19 spread. This brief addresses the following questions? How effective have been stringency index in stemming the COVID-19 pandemic? Given the enormous disruptions in livelihoods, were African governments sufficiently prepared to provide buffers to vulnerable households? What should be the priority in the post-COVID-19 world for African governments?

Figure 1: Mean daily trends in stringency index and mobility of people to retails stores in Africa

Source: author’s computations based on data on Stringency Index and Google mobility data

(https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/ ) in 54 African countries

Has stringency worked in containing infections?

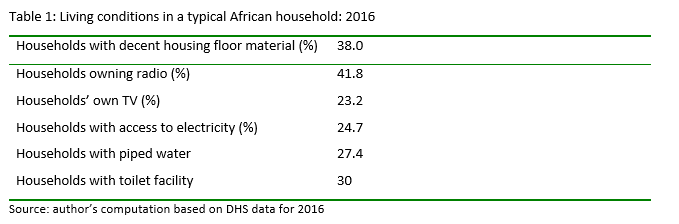

There are credible reasons to think that the WHO guidelines to combat the spread of the virus causing COVID-19 outlined above would work in a setting where living conditions are such that people have access to private living rooms, which helps to isolate infected people; running water in all rooms; access to information (telephone, TV, and other information media); and other amenities. Data from Demographic and Health Surveys for African countries show that most people do not have access to radio, TV, electricity, sufficiently spaced rooms, etc. (Table 1). In this situation, it is very difficult to expect the stringency measures to make much headway in controlling the pandemic.

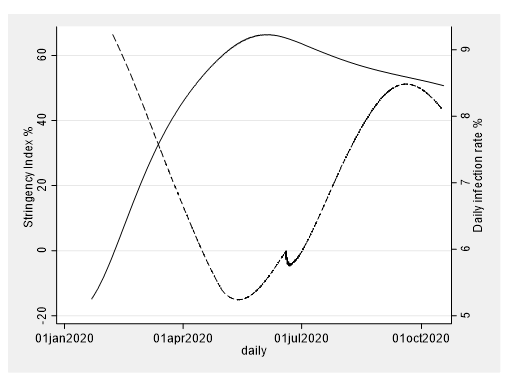

Figure 2 echo these limitations in the context of Africa despite measurement errors in the rate of daily infections which at the initial period focused only on people showing some symptoms as testing capacity was very low. Around April, testing capacity improved significantly in most African countries which was also correlated highly with the stringency index. However, even after April 2020, daily infection rates climbed steadily, while stringency index declined only slightly. The correlation coefficient between infection rates and stringency index was only 12% quite very low. In this regard, stringency measures impacted infection rates quite marginally. One of the lessons learned is therefore how to make stringency measures effective in case such future incidents happen. This include the preparation of the health care system to manage pandemics/epidemics, sensible use of key protective measures, such as masks and sanitizers, educating people on social distancing; sheltering vulnerable groups (the old, the sick and others) in areas where they could be protected from the public, etc.

Figure 2: Stringency index and daily infection rates

Source: author’s computation based on data described above.

Governments could harness the lessons from COVID-19 pandemic to help vulnerable households on a sustainable basis.

The economic consequences of the pandemic have been very well documented. Millions of Africans lost jobs, income, and experienced significant livelihood shocks. Unfortunately, there are no well-designed and functioning social protection programs in Africa that could be invoked at such a time as this. As a result, poverty increased sharply in many countries leading also in some cases to malnourished. Can African governments afford to institute and implement effective social protection programs to fight poverty, provide health care and other basic needs, such as education? A cursory look at the basic statistics and potential of the African economy suggest that it is indeed possible to promote social inclusion and address inequity by blending formal and informal social assistance programs. According to the World Bank, the magnitude of extreme poverty (percent of the population living below the poverty line of 1.9 USD in PPP per person per day) was 34%[2]. The poverty gap, which measures average shortfall of the income of the poor from the poverty line, was 12.7%. Combining the two, it would take 14% of Africa’s GDP transferred to the poor every year to eliminate extreme poverty. Certainly, faster economic growth would help to lift poor households out of poverty on a sustainable basis, but it is not sufficient. Some degree of complementary income transfer, even for the working population may be needed through various social protection programs. This may involve community participation, faith-based organizations, self-help organizations, etc. which could be leveraged to institute a functioning and efficient social protection program. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the potentials of these institutions. Surveys across Africa showed that interpersonal transfers by friends, relatives, family members, self-help organizations, and others provided substantial assistance to the neediest at the height of the lockdowns. This lesson could be harnessed to fight poverty on a sustainable basis using local knowledge, community organizations and government support.

- Evidence from high frequency panel data in several African countries showed lockdowns and other stringency measures led many households to experience hardships

- The Covid-19 pandemic has led to significant disruptions in livelihoods, affected material and emotional wellbeing as well as caused social unrest.

- There have been contractions in economic activities, rise in unemployment, loss of incomes that led millions of households to cut down on their food consumption, miss meals for prolonged period and suffer from emotional distress and anxiety.

- The rise in unemployment in several African countries during the lockdown was unprecedented. Nearly all sectors of employment were affected, evidently some more than others.

- The pandemic has shown also how little trust people have on their government, a critical issue to build a community-government partnership.

What should be the priority for post-COVID-19 recovery in Africa?

- Could African governments have done differently in managing the pandemic?

- How fast recovery could be restored in employment? Which sectors of employment could generate rapid recovery and which ones could lead to permanent job losses?

- What would be the future role of well-designed social protection programs in a situation such as this?

- What would be the potential for community-government partnerships to fight such shocks?

- How could governments protect vulnerable groups, mainly women and children?

- The policy responses particularly lockdowns have led to a significant economic and social disruptions. The evidence on the effectiveness of the lockdowns in containing infection rates was little and at best not strong.

- Governments could learn from this experience in managing future pandemics by implementing smart containment policies that depend on the epidemiological characteristics of a pandemic while maintaining the economy running.

Policy Implications

African governments may not be able to sustain and enforce lockdowns for a period long enough to contain a pandemic considering the huge burden falling on households and the ensuing psychosocial problem it creates (violence, anxiety, and mistrust)

Smart policies require:

- Ensuring readiness of the healthcare system to track, isolate and treat infected persons

- Implementing preventive measures (such as community understanding of the transmission mechanisms, availability of masks and sanitizing materials at affordable prices) with diligence

- Keeping people vulnerable to the virus under special care

- Recovery from the pandemic is a long road ahead for many countries. The challenge is to know the full impact of the pandemic on household wellbeing. Few countries have the necessary information to identify the social groups that carried the burden of dealing with the pandemic.

- Despite the challenges, the pandemic also offers an opportunity to implement innovative social protection programs that target well the vulnerable groups through community-government partnerships.

[1] See the full details of the Stringency Index in Hale, Thomas, Jessica Anania, Noam Angrist, Thomas Boby, Emily Cameron-Blake, Martina Di Folco, Lucy Ellen, Rafael Goldszmidt, Laura Hallas, Beatriz Kira, Maria Luciano, Saptarshi Majumdar, Radhika Nagesh, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, Helen Tatlow, Samuel Webster, Andrew Wood, Yuxi Zhang, “Variation in Government Responses to COVID-19” Version 12.0. Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper. 11 June 2021. Available: www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/covidtracker

[2] See the aggregate poverty computed from Povcalnet (http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/povOnDemand.aspx)

- The ageing population of Africa is increasing, so it’s suffering - October 10, 2021

- Are social protection programs effective in caring for the elderly in Africa? - October 5, 2021

- For whom the bell tolls? Social Protection in Africa during Covid-19 pandemic - September 30, 2021